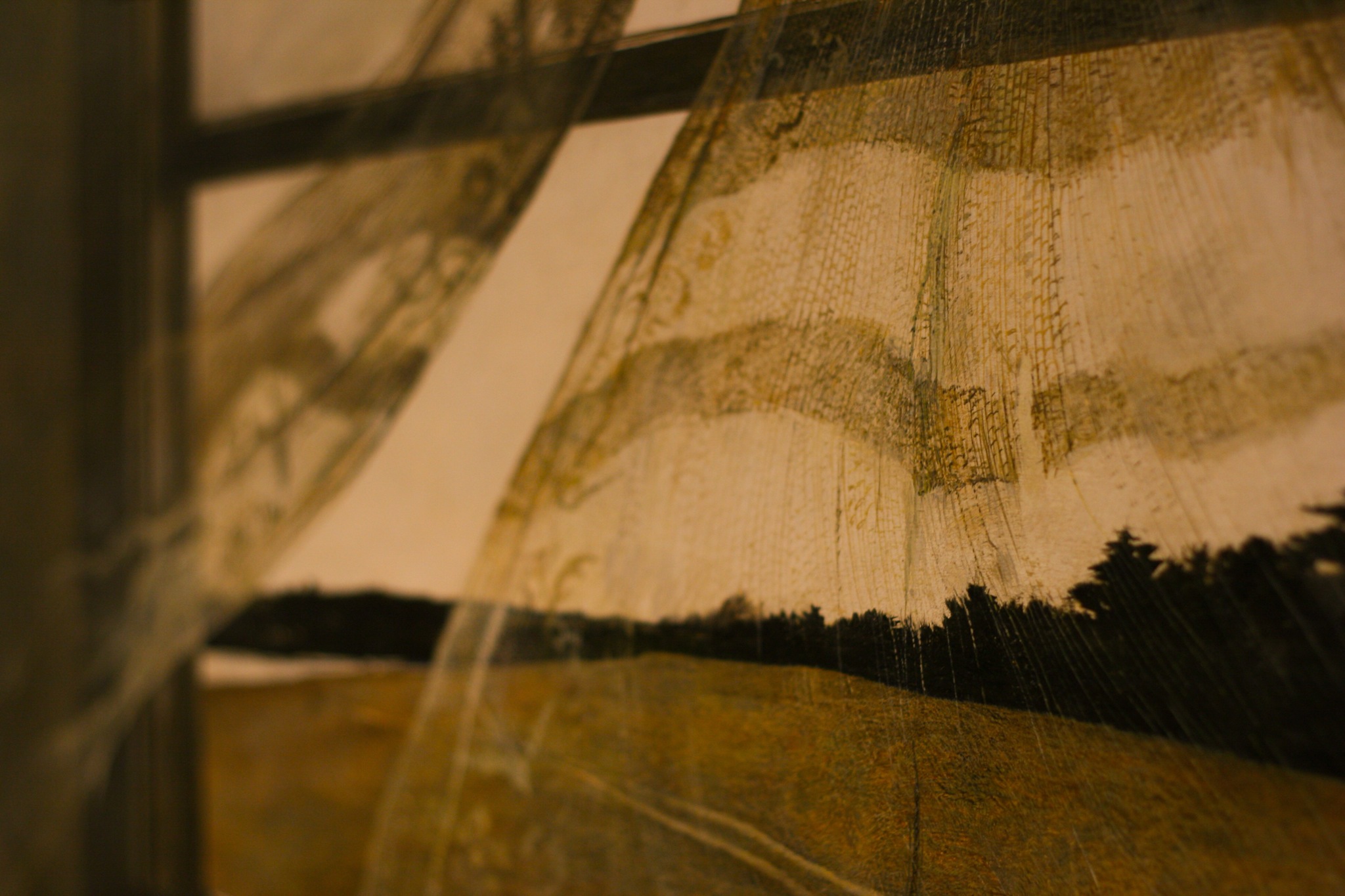

This is a picture of an Andrew Wyeth. I stared at it, at this particular angle, for a long time; examining it with head tilted, then through the camera lens, then squinting, then wide-eyed. This picture renders paint and canvas invisible. They are no longer the mediators of this curtained scene. It is just me, tucking myself behind the curtain to stare at trails and trees. It is me breathing in the fresh air, no paint residue to stale it. It is me observing the pastoral scene sans canvassed limits.

I would argue that Realism (as a genre) succeeds when it removes the obstacle of the medium (paint, canvas, clay, metal) to reveal the transparent image. Well done, Andrew Wyeth.

I would also argue that we’re attracted to Realism because of this very ability to suspend our disbelief; this art feels true to every fiber of our beings, and we want it to be so. It’s serene, crisp, and lovely. It’s better than believing that we’re observing a flat panel fixed to a matte wall. In literature, we call this suspension of disbelief verisimilitude—when an author helps us ignore his fabrications because he has given us a reason to believe, against our better judgment, that his words are true.

In our daily lives, there’s another name for this phenomenon: functional nihilism. “If I don’t think about it, it doesn’t exist.” This is a suspension of our disbelief through willful ignorance. We are choosing to ignore part of the story.

If I don’t think about the canvas barrier that separates me from Wyeth’s pastoral scene, then it doesn’t exist, and I’m whisked away to a world of my own making, one where I don’t have to leave the wooded shelter…ever. You can see the appeal, here.

Freud would call this denial. But that word is overwrought and misses the juxtaposition of violence and pragmatism. We do violence to our memories by sentencing them to oblivion; and we do it practically as a survival mechanism—so we can function.

The heart-wrenching pain of ending a relationship can turn the best of us into functional nihilists. We want to annihilate the beautiful new beginnings that are now sickening and painful. We also want to crush the painful endings that leave us feeling vulnerable and hurt; because to replay them daily, to allow them to be a part of our moment to moment experience leaves our nerve endings perpetually exposed. Who can function when they are perpetually replaying a traumatic scene?

This pragmatism is enacted without discrimination. We willfully forget embarrassing moments, immoral decisions, and guilty feelings as well as major failures, childhood traumas, and relationship endings. This nihilism also applies to procrastination. If we don’t think about what needs to be done, we aren’t obligated to do it.

As with all of our defense mechanisms, we believe the benefit outweighs the cost. But we are blinded to what that cost is, to ourselves and others. Last year I met a woman who shared that she had gone through a bitter divorce. She was happy to declare that she was now “over it”. Intrigued, I asked how she had accomplished this. “I moved across the country.” She said. “Now I don’t have to think about him anymore.” As I listened to her story it became apparent that she had given up a huge support network, a great job, and an established life to get away from her ex-husband. Sadly, in her attempt to avoid one man, she lost almost everything else. And if the payoff was to forget him, it didn’t work. He consumed most of our conversation.

My heart goes out to this woman. Her story, though a dramatic example, is similar to our own. We are oblivious to what we’re sacrificing in our attempts at annihilation. We may not have moved across country, but we have lost out on meaningful living, nonetheless. As for this woman, whenever we engage in functional nihilism it can’t help but impact our relationships, our work, our sense of well-being–our lives.

If we take a page out of Nietzsche’s Playbook, we will find our nihilism expanding beyond the borders. We will find that, over time, what seemed functional now consumes us.

What are those events, relationships, beliefs that you’ve done violence to? If you’re honest, what have you lost in the aftermath of your annihilation?

So as not to leave us in the abyss, this is only part of the story. We can move beyond functional nihilism to embrace growth and healing. We can overcome our propensity to avoid. When we do, we no longer have to suspend our disbelief, because the healing is tangibly, palpably, and delightfully real.